“It’s in the darkest moments when the cracks allow the inner light to come out.”

-Edward James Olmos

Crack Open Carefully— And Do Not Break!

A few years ago, Epicurious invited 50 people into their studios to attempt at cracking a walnut. The participants engaged a wide range of tools and devices—hammers, knives, mallets, meat tenderizers, screwdrivers, and fingers were all painstakingly employed to try to crack open these hard shells. Any hesitation or restraint resulted in the shells being left completely intact. An overzealous approach busted the shells but simultaneously smashed the walnut kernels as well. The Federal Reserve is facing a more complicated but somewhat related dilemma: try to crack down on stubborn inflation without destroying the heart of the economy.

They began the process more gently, with a 25bp hike in March then followed by a 50bp hike in May. As that had seemingly no initial effect, they became more aggressive, hiking 75bps for three consecutive sessions while also tapering the Fed’s balance sheet—first by $37.5bn monthly from June and then $95bn monthly starting September.

While slight cracks in inflation are starting to appear, it is seemingly not yet enough. Prices are still rising over 8% from a year ago, and so the Fed intends to continue to pound hard by tightening monetary policy. With another 75bp hike appearing likely in November and more hikes expected in the months thereafter, investors are left wondering if the Fed might be doing too much?

Missed the Mark

Last December, Fed officials released their final Summary of Economic Projections for 2021, and along with it, their dot plot—a forecast for where interest rates would go in the coming years. The prevailing prediction was that the Fed Funds rate would increase to 0.75%-1.00% by the end of 2022, a view shared by 10 of the 18 Fed members.

With the Fed Funds rate now at 3.00-3.25% and expected to end up over 4% by the end of the year, those predictions are unflattering at best with the benefit of hindsight. It is clear that even less than a year ago, the Fed greatly underestimated the depth and persistence of the current inflation crisis. Now the central bank is playing catch-up and embarking on its most aggressive monetary tightening mission since 1980, which at the time resulted in consecutive recessions in back-to-back years.

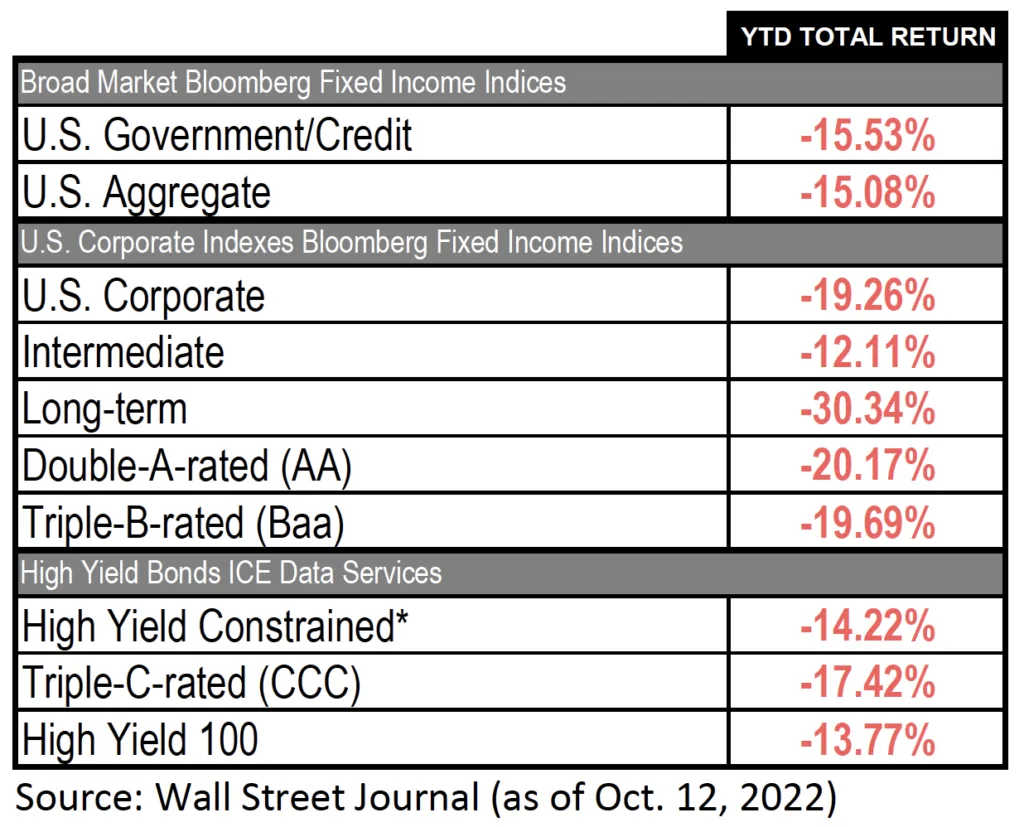

While stocks have already been flailing in a bear market for months and bonds have suffered their worst performance this year since 1949, the real economy has been resilient, perhaps stubbornly so. Although economic growth has declined two consecutive quarters, the unemployment rate remains historically low at 3.5% and wages are still growing close to 7%, defying the classic telltale signs of a recession. A real recession, accompanied with job losses, pressure on wages, and earnings cuts is looking increasingly likely to creep up next year.

Just a Small Crack in Earnings (For Now)

During the third quarter, analysts slashed their earnings estimates by 6.6% for Q3 and are forecasting S&P earnings of $234.83 over the next 12 months (according to FactSet), which many investors fear is still too optimistic. Historically, earnings have fallen nearly 30% on average in recessions, with a median decline of closer to 18%.

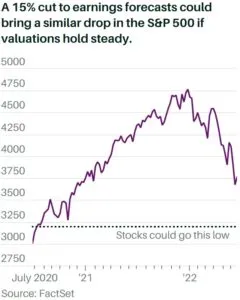

Most forecasters are assuming a more mild recession, with many strategists are assuming declines of closer to 8-10%. This earnings season will likely provide greater visibility as companies give further guidance. A report from Barron’s this summer explored the scenario of a 15% reduction in earnings.

Still Work to be Done on the Labor Market

The labor market in the US has remained particularly tight throughout the year. With unemployment at just 3.5% and job openings still vastly outweighing the number of individuals looking for work, wages have continued to push higher. Fed officials are seeking to bring wages down as a way of reducing consumers’ spending power to ease inflation. The Fed has articulated its target of bringing unemployment to 4.4% by the end of 2023. Meeting this goal would require close to an additional 1.5 million unemployed individuals—either in the form of job cuts or new individuals entering the workforce unable to find employment. While the number of monthly job gains has been slowing, net job losses remain elusive but appear increasingly likely next year.

Before this is expected to happen, though, job openings need to slow as well. After rising somewhat steadily for nearly two years, job openings have started to roll over since March, which coincides with the Fed’s first initial rate hike. Most recently in August, job openings declined by 10% to 10.1 million in a single month. With the unemployment rate at 3.5%, there are roughly 5.6 million people looking for work, which would imply job openings theoretically need to fall closer to this level or lower to pull up unemployment.

Global Ripple Effect

Aggressive rate hikes from the Federal Reserve, intended to directly address domestic inflation, has pushed the value of the dollar significantly higher as investors flock towards the US dollar as a safe haven. While higher rates imply a greater cost for the US to service its record $31 trillion of outstanding debt, its stature as the world’s primary reserve currency has only been reinforced as other major currencies such as the euro, yen, and pound have all fallen dramatically this year.

A strong dollar, however, does not bode well for many multinational US companies selling goods and services abroad. These currency headwinds are expected to weigh on corporate earnings in the coming quarters and several companies have already warned that the dollar will hinder revenue generation.

A Market Revaluation

Higher rates have also put pressure on stock valuations. The S&P’s forward PE multiple has fallen ~17% since the start of the year, accounting for roughly 2/3 of the price decline thus far. Bonds have had a comparably challenging year and have fared even worse in historical terms, down the most in over seven decades.

Not So Atypical for a Midterm Election Year

Historically, midterm election years have not been kind to the stock market. Dan Clifton as Strategas observed that the S&P 500 has declined 19% on average within the midterm election years since 1962. The potentially good news is stocks have historically bottomed in October and have rallied by nearly 32% over the following 12 months. In fact, Clifton points out that stocks have been positive in the year after every midterm election since 1942.

Things May Get Worse Before They Get Better,

But They Will Get Better

While the current inflationary environment has drawn comparisons to the period of the 1970s-80s, the situation presented four decades ago was arguably far more daunting. The unemployment rate at the time frequently hovered between 8-10% and the US consumer was considerably worse off. Furthermore, the US was at the heart of the world’s geopolitical conflicts—stuck in the Vietnam War until 1975 and the Cold War with Russia until 1991.

Nevertheless, it would be unwise to diminish the challenges we presently face. Excess savings from the pandemic are dwindling and growth is showing clear signs of slowing. Company earnings may decline and jobs may be lost. But these are the economic cracks necessary to move past this challenging phase. Eventually inflation will break and the current economy is in position to recover as monetary policy finds stability once again.

The Fed has a tough nut to crack; but it’s cracked tougher ones before.